The Lessons of the Gulf of Tonkin

A study of crisis, power, and the narratives that shape public trust

The first reports about the attacks in Venezuela arrived on September 2, 2025 with the haziness and uneven detail that characterizes many emerging foreign policy stories. Officials within the Trump administration announced that a United States operation had disabled what they identified as a dangerous drug vessel. Very little intelligence was released to the public, and many assertions were made quickly. Explanations lacked depth with the structure of this moment feeling too familiar. It resembled earlier episodes in which claims of aggression abroad produced swift political reactions at home. The comparison was not exact, yet the echo was unmistakable. It pointed back to one of the most consequential foreign policy crises in modern American history, the Gulf of Tonkin Incident of 1964 and the congressional resolution that followed it.

To understand that moment, it is necessary to recall that American involvement in Vietnam did not begin in August of that year. For more than a decade, the United States supported the Republic of Vietnam through financial aid, military advisers, and covert activities along the coast of North Vietnam. These operations intensified during the John F. Kennedy administration and continued into Lyndon Johnson’s presidency. Covert maritime actions known as Operation 34A placed pressure on North Vietnam and created a tense environment in which American naval vessels gathered intelligence. By the summer of 1964, the region was saturated with suspicion and conflicting intentions. President Johnson faced a strategic dilemma where he wished to avoid a dramatic escalation while also avoiding any impression of weakness during an election year. This balancing act set the stage for the events that followed.

President Lyndon B. Johnson with an American soldier in Vietnam; SOURCE: NYT

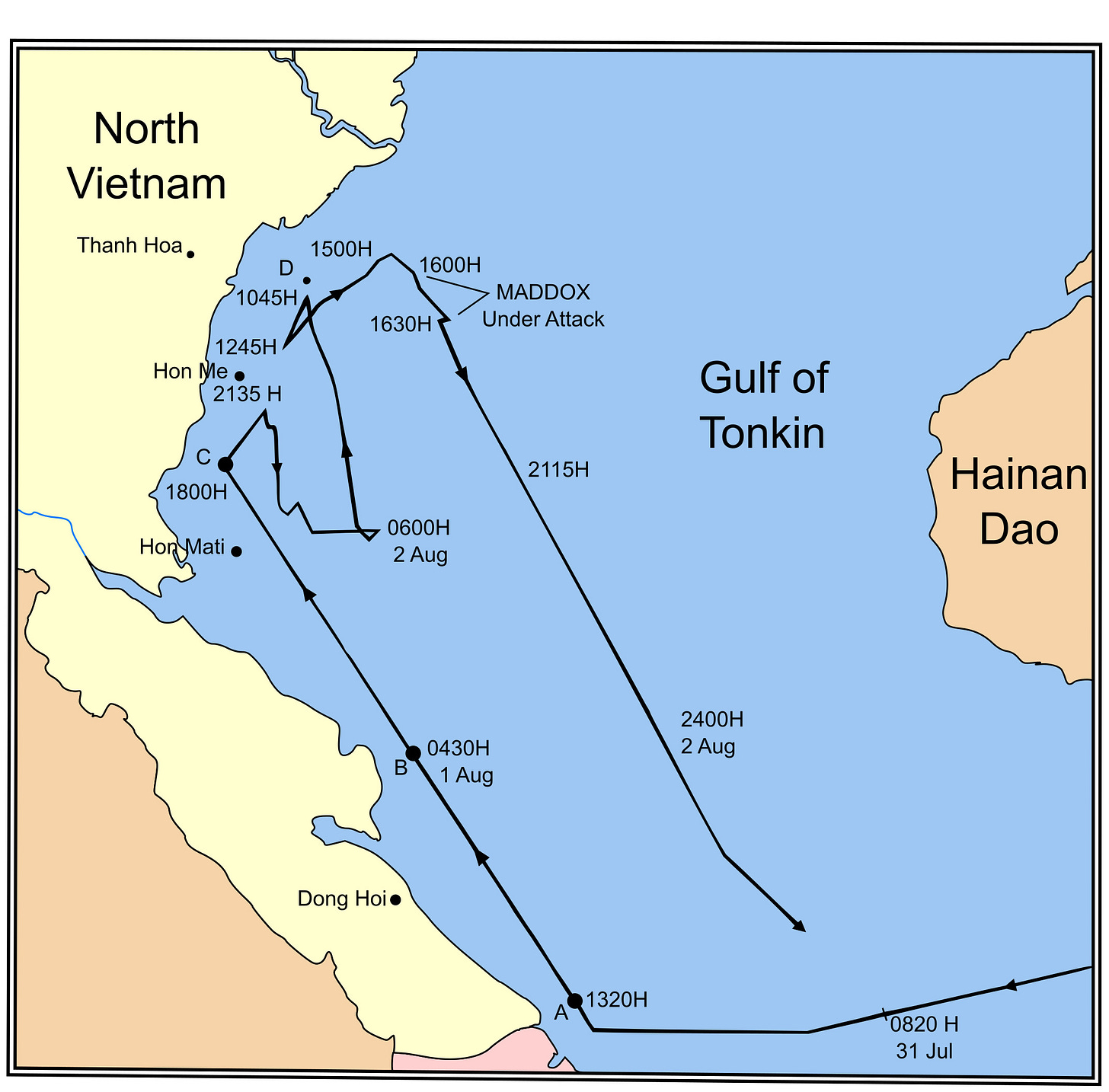

On the second day of August, the destroyer USS Maddox encountered three North Vietnamese patrol boats while operating in the Gulf of Tonkin. Shots were exchanged. The Maddox reported that it had come under attack and returned fire, damaging the vessels. This first incident certainly took place, though later investigations revealed that the broader context was more complicated than initial reports suggested. North Vietnamese forces were aware of the American backed raids taking place along their coastline, and the presence of the Maddox carried implications that were not widely communicated to the public. Still, the Johnson administration presented the incident as a clear act of aggression.1

Two days later, the situation became far more complex. The Maddox and another destroyer, the USS Turner Joy, reported that they were again under attack. Radar images seemed to show incoming vessels. Sonar readings suggested hostile activity, and crew members caught glimpses of what they believed to be patrol boats advancing through the night. Within hours, doubts surfaced among officers and intelligence analysts. Some on the ships questioned whether any attackers had been present. Storm conditions, irregular radar returns, and human error created an illusion of danger. Analysts at the National Security Agency were uncertain almost immediately, and their later reports reflected this ambiguity.2 Despite this uncertainty, the Johnson administration announced that a second attack took place and framed it as evidence of escalating hostility.

The American public received the mainstream narrative at face value. Newspapers reported the administration’s claims with confidence. Television broadcasts echoed the official account and the Cold War context reinforced a sense of urgency. Many Americans believed the nation was engaged in a global contest that required decisiveness and vigilance. The idea that communist forces had attacked a United States vessel resonated strongly.

President Johnson responded by asking Congress for authorization to take all necessary measures to repel armed attacks and prevent further aggression. The resolution that emerged, known as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, was brief yet expansive. It passed with overwhelming support. In practice it gave the President broad authority to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia without further congressional debate.3 Johnson insisted that the measure was defensive and limited. In reality, it became the legal foundation for a vast escalation.

Public opinion initially supported the administration’s approach. Editorials praised the firm response and the narrative of unprovoked aggression shaped early perceptions of the war. Only later did discrepancies become widely known. The Pentagon Papers revealed that the administration had not fully disclosed the uncertainty surrounding the second attack.4 These revelations created a profound shift in public trust and intensified skepticism regarding presidential power and intelligence claims.

Historians have since examined the Tonkin episode through multiple lenses. Fredrik Logevall and others noted that the administration faced significant strategic pressure.5 Some advisers argued that escalation was necessary for geopolitical credibility while others urged caution. The Tonkin events provided momentum for those who favored stronger action. Scholars have also explored the structural tendencies within the American political system that allow executives to shape narratives during crises. When intelligence is unclear, leaders may present selective information, and legislatures often defer to the executive when told that national security is at stake.

Tonkin reveals a pattern that appears across different eras. Intelligence that is ambiguous or disputed is sometimes framed as certain. Crises unfold quickly. Action often precedes full debate. Only after decisions have been made do questions arise about the reliability of the initial claims. This rhythm has returned in various forms throughout American history. The recent reports from Venezuela contained faint traces of this structure. Officials made urgent claims. Intelligence was not released. The justification appeared before a broader public discussion could develop. The resemblance was not literal but structural.

The enduring lesson of Tonkin is that narratives created during the earliest hours of a crisis carry enormous power. They shape public expectations. They influence legislative decision making. They expand or contract the reach of executive authority. A democratic society depends on critical evaluation during such moments, yet the pressure of urgency often narrows the space for careful reasoning. Historical memory serves as a safeguard. When citizens recall how narratives influenced the path to war in the past, they are better prepared to examine contemporary claims with clarity and restraint.

Tonkin remains a cautionary example of how foreign policy decisions can hinge on uncertain information and how quickly power can expand when danger is framed as immediate. It demonstrates the importance of skepticism, oversight, and transparency in democratic life. The faint echo that appeared during the Venezuela incident was not a sign of repetition but a reminder. It urged a return to history to understand how narratives of crisis are formed and why their earliest moments matter most. Memory does not predict the future, yet it sharpens awareness and helps ensure that decisions are guided by understanding rather than haste.

“Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, 1964,” Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/gulf-of-tonkin.

Gulf of Tonkin Incident,” National Security Agency Declassified Documents, https://www.nsa.gov/Helpful-Links/NSA-FOIA/Declassification-Transparency-Initiatives/Historical-Releases/Gulf-of-Tonkin/

“The Gulf of Tonkin, Forty Years Later,” National Security Archive, George Washington University, https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB132/.

National Archives and Records Administration. “Pentagon Papers.” https://www.archives.gov/research/pentagon-papers.

Fredrik Logevall, “Provocations: AUGUST 1964.” In Choosing War: The Lost Chance for Peace and the Escalation of War in Vietnam, 1st ed., 193–221. University of California Press, 1999. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.5973212.13.

Wonderful edition, as usual my friend!