The Boy Mayor in New York City

The city once trusted a 34-year-old reformer to rebuild itself. A century later, it’s doing it again.

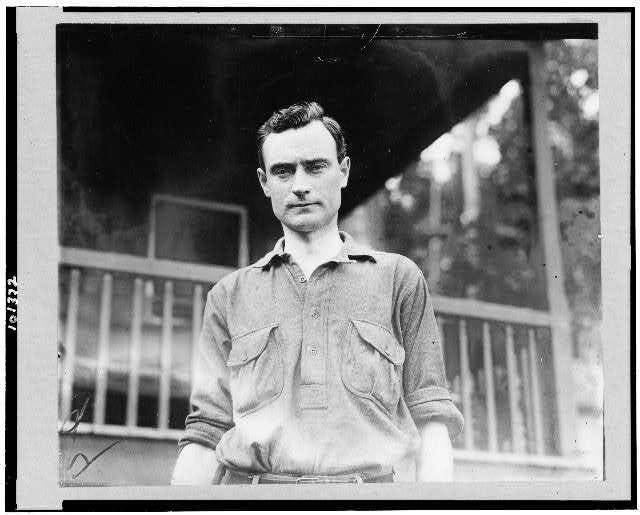

When New York City elected Zohran Mamdani, a 34-year-old and the city’s first Muslim and first South Asian mayor, it marked more than a milestone in representation. It revived an older civic pattern: New York’s recurring faith in youth and reform when its machinery feels tired. The last time the city made such a leap was over a century ago, when another 34-year-old, John Purroy Mitchel, took office in 1914.

While they belong to vastly different eras, both men emerged in moments when New York seemed to be questioning whether its institutions could keep pace with its own size — a city turning to youth to make itself new again.

A City in Motion

Mitchel’s New York was a restless place. The five boroughs had only been joined sixteen years earlier, and the city was still figuring out how to govern itself as a single organism. Mitchel, nicknamed the Boy Mayor, ran on reform: anti-corruption, efficiency, and modernization — the watchwords of the Progressive Era’s civic faith.1

His administration lives on in extraordinary detail. The New York City Municipal Archives preserves 127 cubic feet of records from his term that includes correspondence, board minutes, and departmental reports that read like the blueprints of a city being invented.2

Among the most visible projects of that period was the expansion of the subway through the Dual Contracts. These were agreements with private operators signed in 1913 that effectively doubled the system and extended it into the outer boroughs.

The idea was revolutionary: transit could make the newly consolidated city real by binding its edges to its center.3

Another achievement came in 1917, when Mitchel presided over the ceremonial opening of the Catskill Aqueduct, bringing clean mountain water to the metropolis. The event, documented in a civic souvenir volume published by the mayor’s office, turned infrastructure into celebration.4 In both projects, the city expressed a belief that engineering and governance were two sides of the same promise.

Mitchel’s reforms went beyond construction. He reorganized departments, dismissed corrupt borough presidents, and implemented the city’s first zoning regulations which were meant to make government rational, professional, and less beholden to patronage.5

The Machine and Its Maintenance

Fast-forward to 2025. New York has long since built its bridges, tunnels, and skyline, but the problems are uncannily familiar. Subways strain under deferred maintenance, housing costs suffocate families, water tunnels a century old await repair, and climate resilience has become the city’s newest infrastructural frontier.

Into that reality steps Zohran Mamdani who is young, reform-minded, and promising renewal. His campaign drew from the language of fairness and functionality, appealing to voters who felt that the city’s bureaucratic machinery no longer matched their daily experience. Just as Mitchel once embodied the Progressive Era’s faith in modernization, Mamdani arrives as the figurehead of a 21st-century city asking whether it can still work as it should.

The continuity is striking: a youthful mayor comes to power in a moment of infrastructural fatigue, promising to re-tune the city’s engine.

That Mamdani’s victory comes twenty-four years after 9/11 makes it one of the more symbolically charged elections in New York’s modern history. The city that once became a national emblem of grief and suspicion toward Muslim communities has now elevated a Muslim mayor. It is, in a sense, a moment of reckoning and reconciliation with not only with national narratives of identity, but with the city’s own complex relationship to belonging and fear.

In the two decades following the attacks, New York’s Muslim population immigrants from South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa lived both within and against the mythology of the “city that never forgets.” Neighborhoods like Astoria, Jackson Heights, and Bay Ridge became home to vibrant Muslim communities even as surveillance programs and prejudice persisted. Mamdani himself, an immigrant and son of Ugandan-Indian parents, built his political base in Queens, the borough most emblematic of that pluralism.

His election thus operates on two registers: political and cultural. Politically, he represents a new urban progressivism focused on housing and transit equity; culturally, he stands as evidence that the city’s identity continues to stretch and absorb. The same metropolis that once mapped “suspicious activity” around mosques now celebrates a mayor sworn in under their domes.

For New York, this is not amnesia but growth of a slow civic re-imagining of who counts as the face of the city.

Reading the Archive

What makes Mitchel’s story especially tangible is that we can read it. The Municipal Archives’ digital portal hosts letters, proclamations, and reports from his term, showing a young administration trying to master the complexity of modern governance.6 There’s a letterhead, ornate and civic; a memo on salary reform; an audit on water pressure. Each is a fragment of the larger machinery of municipal life.

These records are not mere curiosities but they reveal the administrative texture behind grand ideals. The faith that good paperwork, good plumbing, and good politics belong together may sound quaint now, but it was foundational to New York’s self-image as a city that could build and maintain at scale.

Today, that same faith survives in a digital form. Instead of archives, we have open-data portals, budget dashboards, environmental reports, and social media which are all part of the same civic hope: that if the city can know itself, it can fix itself.

Mitchel’s story, however, ends abruptly. After one term, his reform coalition fractured; the city’s political tides turned against him. He lost reelection in 1917 and died the following year, at just 38, in a military training accident. His legacy became a cautionary tale about idealism colliding with entrenched systems.

That tension between vision and durability will shape Mamdani’s term as well. Youthful energy may spark reform, but institutions move slowly, and New York’s civic machinery, like its infrastructure, tends to outlast its operators.

Every few decades, New York rediscovers this cycle. When it begins to doubt its ability to govern itself, it turns to a young leader to prove otherwise. In 1914, that leader was John Purroy Mitchel. In 2025, it is Zohran Mamdani. Both arrived when the city felt too complex, too crowded, and too in need of faith in its own future.

The parallel is not coincidence but character: New York is a city that believes in repair. It builds, decays, rebuilds, and insists that its next act will be the one that gets it right.

If Mitchel’s water tunnels and Mamdani’s transit pledges share anything, it’s this: both imagine a city that can still reinvent itself, even after a century of trying.

Sources

See documents for the contracts here: “The Dual Contracts,” NYCSubway.org

New York City has an expansive amount of collections that are worth exploring: NYC Municipal Archives Digital Collections Portal

Amazing Ethan!! So we'll written as usual. Love, Grammy