The American Revolution and How We Remember It

Review of the book "The Memory of '76: The Revolution in American History," by Michael D. Hattem

On January 29, 2025, President Donald Trump issued an Executive Order that “Ends Radical Indoctrination in K-12 Schooling” that specifically emphasizes a ““Patriotic education” that presents the history of America grounded in: an accurate, honest characterization of America’s founding and foundational principles” and “a clear examination of how the United States has admirably grown closer to its noble principles throughout its history.”

Donald Trump’s view of a patriotic education portrays constant American excellence, but in truth, that is only one half of the story. The darkness of our past is not unpatriotic, and highlights the change of where we as a country came from. Understanding both helps students develop their own reasons why this country is worth living in; why America is the home of liberty, and how we can uphold the values that are central to us.

In addition to these principles is the reestablishment of the 1776 commission that started in 2020 to combat the conversation surrounding Hannah Nikole-Jones 1619 Project.1 Trump, along with many other conservatives, believe that the United States and its history education has built a curriculum on guilt rather than critical thinking. The order states that no one “should feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress because of… actions committed in the past.” Trump and his supporters are convinced that history rewritten in the classroom, and that we are living in a time where students are taught to hate their country.

As a history teacher, I know this to be false and a direct attack on educators and historians alike. What I teach is the truth—both sides of the coin in order to present to students the bright and dark moments of our nations past. This includes slavery, racism, sexism, war, and violence. But it also includes political unity, memory, and movements. Teachers describe the history of the nation as it was in order to explain why it is. With the 250th anniversary of the United States’ birth happening next year, conversations from historians, teachers, politicians, citizens, and anyone interested, creates an in depth analysis of every part of the Revolution. From the military battles, political animosity, and various perspectives of individual lives, the Revolution is viewed from so many angles. The Revolution in our American memory is in the fabric of every movement. But how Americans remember the Revolution has dramatically changed over the years.

The development of how America views the Revolution throughout history is the subject of Dr. Michael Hattem’s latest book, The Memory of ‘76. He is a historian of the Revolution and historical memory, and this book is right for the moment. Hattem argues that “the memory of the Revolution has often done more to divide Americans than to unite them” as remembering the Revolution helps to revise a nostalgic tone of the past.2 That tone is what Hattem further explains throughout his book.

The memory of the American Revolution began as soon as the country was built by the United States Constitution. Hattem often utilizes the celebration of the Fourth of July as the focus of a lot of his analysis, as it showcases the development of our commemorations of the Revolution. Almost immediately, Americans used the past to fuel partisan division. Boston, Massachusetts claimed the origin of the Revolution, and more celebrations were held in Boston than anywhere else in the early Republic.3 Tensions between the working class members and Boston Federalists elites caused a rift in how Boston used the memory to remember why the city rebelled in the first place.

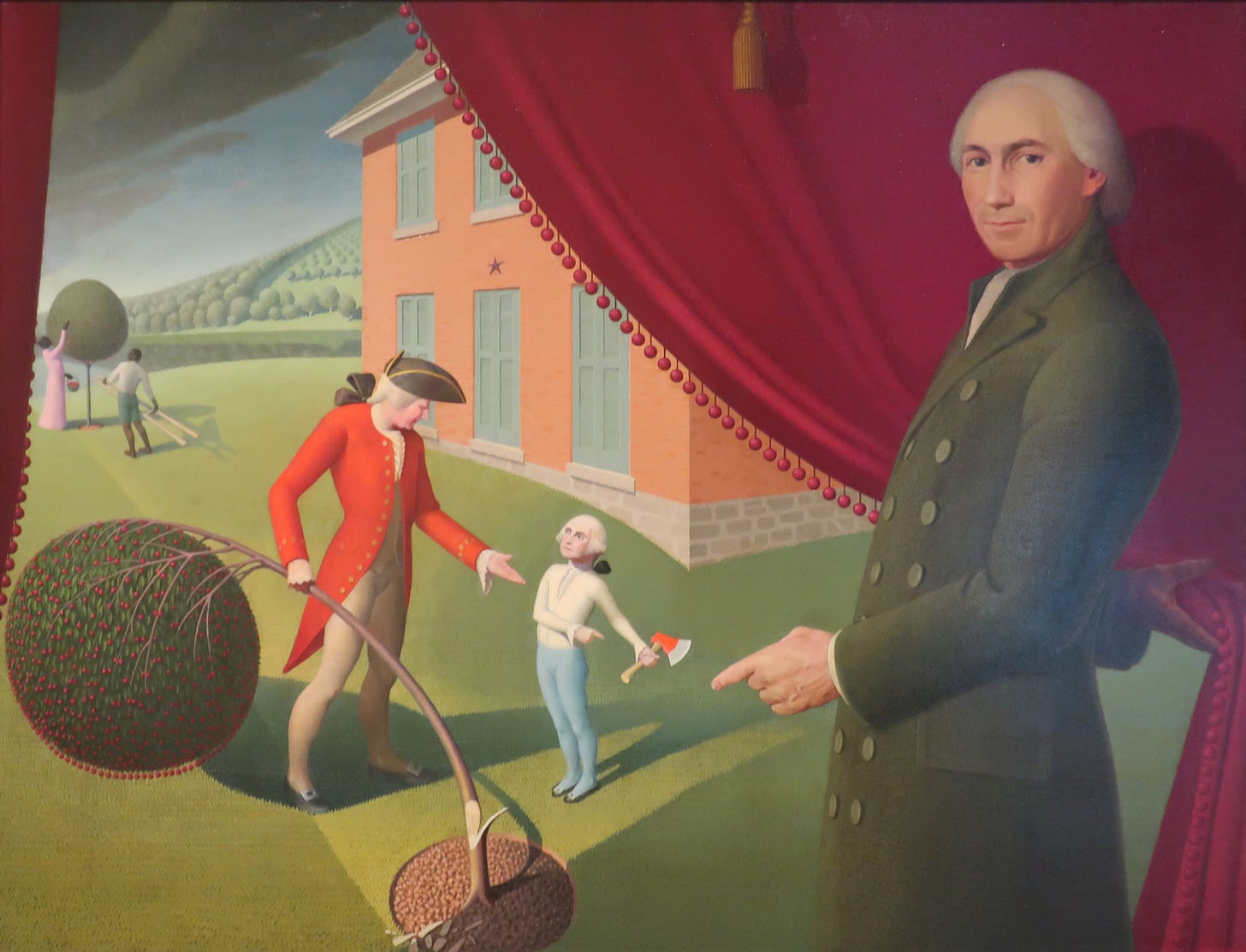

Commemorations became more popular after the death of George Washington. When he was alive, he valued his image and by the time of his death, he became the most revered man. Americans reflected on his death as a national unifying event. Americans mystified him with stories, coins, stamps, names, and all kinds of printed material. Decades after his death, a writer named Mason Weems wrote a biography of George Washington—often considered to be the first one—and utilized a lot of fictional stories to expand his work. The Washington in his book was a mythical and untouchable figure. A lot of the stories were false in nature, including the infamous “cherry tree” story where it proved Washington was an honest man. Weems’ book was initially aimed at children, but soon became the most popular book for all ages in the early Republic. The death of Washington helped to create a national identity, and influenced many Americans beliefs of how the Revolution—and soon the Founders as a whole—was remembered.4

This is one of many stories that Hattem discusses in his book, as he chronologically discusses the memory of the Revolution. The stories he tells are important, as the memory influences the development of organizations like the Daughters of the American Revolution and eventually Sons of the American Revolution. Revolutionary War veterans began to write themselves back into history when they told their stories through the application of war pensions. The National Archives holds thousands of these stories of veterans who simply looked to survive financially, but offers a rich history of individual personal experiences.5

By the time the American Civil War began when America was most divided, both Union and Confederate soldiers relied on the vitality of the Revolution to influence their cause. Confederates used the memories of their forefathers to promote sectional pride. Both sides also used the the Declaration of Independence to emphasize their cause which effectively unified them. Lincoln, too, often read Washington and Jefferson to help him craft decisions.

Michael Hattem wrote a necessary book, and while I’d love to provide an overview of each argument, I think it is best you buy and read this book yourself. This, more than ever, is required reading for all Americans. As we reflect on the current state of our Republic, regardless of political affiliations, remembering the Revolution is one step of the process. Understanding how we’ve celebrated describes an America that has always held contention with American history, even while it was being written. What Hattem’s book tells us is that the memory of the Revolution, how we teach, celebrate, and interpret has dramatically portrayed continuity while developing change.

You can buy a copy of this book here. I do not make any money for the link.

Joe Biden upon entering office in 2021 disbanded it, and Donald Trump reinstated it in January of 2025.

Hattem, The Memory of ‘76, p. 8.

Hattem, The Memory of ‘76, p. 17.

Hattem, The Memory of ‘76, p. 29.

Hattem, The Memory of ‘76, p. 36.