Mothers of the Early Republic

Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, and Republican Motherhood

This essay was written for a graduate school course. It has a formal tone, quotations, and citations in Chicago Style (17th edition). At the end, there are suggested books for you if you’d like to learn more about the subject. None of the language or wording has changed and remains as it was written by its author.

After failures to publish it in various academic journals for the last year because it “lacks interest” for a general audience, I am publishing it myself. Rejection letters are always a bit discouraging, especially when you are so proud to share your research with the world. As a historian, my interests are Early American New England, and the Adams Family has always fascinated me as a study. My undergraduate thesis was based on John Adams retirement and a lot of my graduate work always goes back to them. This time, I was interested in understanding Abigail Adams a bit more under the concept of Republican Motherhood—an integral part that women played in the development of the United States.

When I started my research, I was interested in the development of American Identity in the early years of the United States. A deep research dive led me to the relationship between Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren (the subjects of this paper). While reading their letters, I found an underlying theme of feminism, motherhood, and politics. This attracted me because of the different perspectives on what a woman’s role was in the Early Republic, and I wanted to know their developing thoughts on the subject. This essay is the result of that research.

On July 25, 1773, two years before the United States declared its independence, Mercy Otis Warren wrote to Abigail Adams that the responsibility of a mother was to “rear the tender plant and Early impress the youthful mind” and if lucky enough, the children would “become useful in their several departments on the present theatre of action.”1 This letter sparked a friendship that was cultivated through the ideals of what a woman’s role was in the Revolutionary Era. Through hundreds of letters, both Warren and Abigail2 wrote about how the work of their husbands, James Warren and John Adams, was influential to the state of the newly created nation. Both women believed that their husbands endured a positive place in history, and both were incorrect in that assumption.3 And yet, by the time of the establishment of the Early Republic in 1789, Mercy Otis Warren and Abigail Adams began to question their own role in the ideals of a country.

Women by 1789 were encouraged to “commit themselves politically and then justify their allegiance,” which created an interest in what a woman could be in the Early Republic.4 In the wake of the republic, an idea called “Republican Motherhood”5 spread throughout the United States and into the homes of women. This ideology sought to prioritize the role women played in the Early Republic and to the development of American values. Women became the center of this ideological shift in how gender dynamics were perceived and revealed after the Revolutionary War. Both Mercy Otis Warren and Abigail Adams influenced their husbands’ ideas and both of them understood that a woman’s role in the Republic was not just dormant inside the home but active within the gears of American society and its politic.

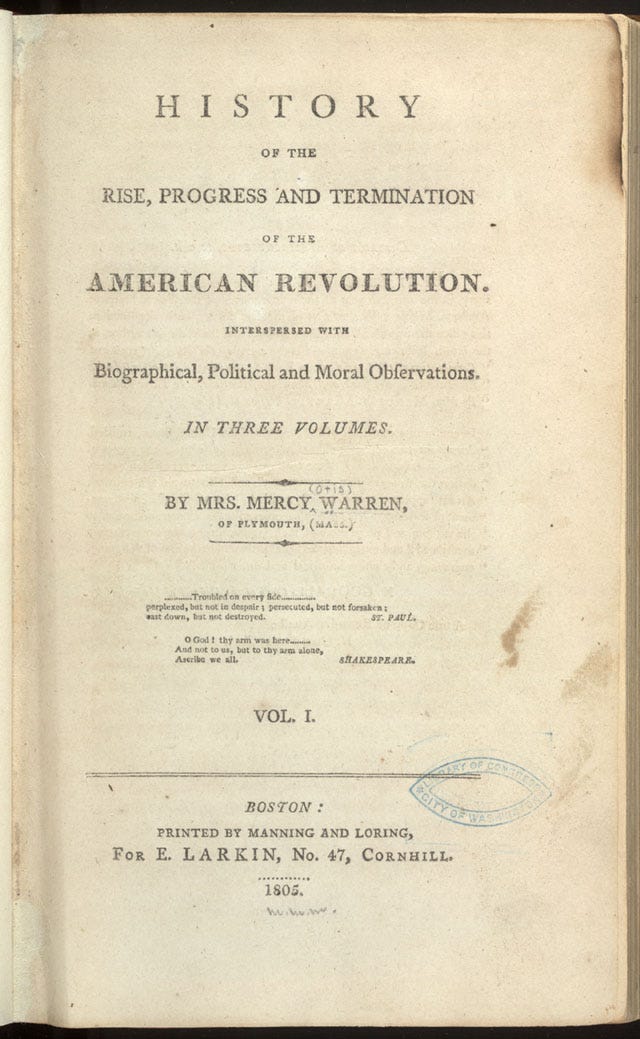

This essay argues, through the lens of their friendship, the degree that Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren understood the concept of “Republican Motherhood” and how it developed their own American Identity. This essay gives a large emphasis to the role Abigail and Warren played in their own lives, but also how that can help us understand the broader role of women. Both women were revolutionary in their own right—Abigail Adams consistently argued to her husband to “Remember the Ladies” while he argued for independence and used her platform as a wife to enhance the importance of women’s education and autonomy in the development of a republic.6 Warren was a poet, playwright, and historian who wrote the first history of the American Revolution called History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution, in which she laid out her personal thoughts on the war. She was severely critical towards John Adams and even George Washington, which caused a disruption between the friendship of Warren and both Adamses.

Both women used the ideals of Republican Motherhood to further and develop their own identity as Americans in the age of the New Republic. Seen through letters, diaries, and even published works, the ideals of Mercy Otis Warren and Abigail Adams are not theirs alone. With the friendship came an understanding of what it meant to be a woman in the early days of the United States. The friendship they created was one that resonated throughout the Early Republic because it helped understand the broader movement and ideology of women. By understanding their friendship, the ideals of the Early Republic became apparent, understood, and expanded as the perspective helped form an original American identity.

The friendship between Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren began just prior to the American Revolution. The two met through the inner political circles that developed in the late eighteenth century as a post-war response to women’s political candor. Many men believed that women did not have political responsibility in the Early Republic, and thus lacked the necessary skills to combat the politics of the day.7 These circles provided women access to political discourse and socialization.

Women from all classes gathered to not just discuss the politics but engage in how these discussions can influence the basis of their homes. These circles did not change their domestic identity as wives and mothers but challenged the ideas of how domesticity influenced the balance of power.8 Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren are prime examples of how that transformed identity persuaded deeper Republican values.

Both women were part of a larger family that was heavily involved in politics. Abigail was married to John Adams who was a lawyer and politician, and she grew up in a family dominated by politics through her relation to the Quincy’s of Massachusetts—a large name in Massachusetts politics. Mercy Otis Warren was married to James Warren who was a merchant, politician, and respected military officer of the Revolutionary army. Her brother, James Otis Jr., was of similar acclaim as he was a staunch Patriot and lawyer in Massachusetts.

Both Abigail and Warren understood the value of politics, civics, and virtue through the work of their family early on. Both women, though, believed that the importance of politics and virtue began with the children they raised at home. In the first letter Abigail Adams sent to Warren, she suggested a book titled On the Management and Education of Children which detailed innovate ways to educate children from the female perspective. Abigail complimented Warren’s ability as a mother and said that it does “not [come] from an opinion that you stand in need of such an assistant… [but] tell me whether it corresponds with the plan you have prescribed to yourself.” Warren’s reply to Abigail was candid, as she explained to her that she still has little idea the best way to be a mother, and that she “must acknowledge I fall so far short of the Methods I heretofore Laid down as the Rule of my Conduct.”9

It was not long before the two women discussed politics. In December of 1773, Abigail wrote to Warren about the deeper restrictions imposed by the British. Adams discussed that “it will greatly aggravate your anxiety to hear how much [the colonies] is now oppressed and insulted.”10 The discussion of politics throughout their friendship was a steadfast comprehension of how they viewed the world. Both women debated the ideas of the Revolution and what it meant to be a woman in the days of oppressive laws.

In the Early Republic, many marriages were set to the law of coverture which emphasized patriarchal control over women’s assets, and while it was shaped as protective, it stripped a woman’s independence.11 Even so, neither Warren nor Abigail were afraid to discuss politics with the men in their family. In a lengthy letter to John Adams in 1780, Abigail Adams wrote about local politics in Massachusetts—admittedly, John Adams favored local politics than national, so he relied on Abigail to keep him informed about their home state—and how she viewed national politics in context of the war. “What a politician you have made me,” Abigail Adams wrote, and “if I cannot be a voter upon this occasion, I will be a writer of votes. I can do some thing in that way but fear I shall have the mortification of a defeat.”12 Abigail understood that while she could not vote, she expressed her grievances to those who can. Through letters and political circles, she was able to understand the depth to which her voice mattered. If not to her husband, then to the people that surrounded him. If not to them, then their wives, mothers, and sisters as a sound board.

Mercy Warren discussed politics with her brother, James Otis Jr. who was involved in the creation of the United States. James Otis Jr. and her husband James Warren encouraged her to engage in politics in the public sphere. A prolific writer, she wrote numerous plays that were published throughout the Revolutionary era into the Early Republic. James Warren called his wife “the scribbler” because she was fast to comment on political actions and ideas.13 This motivated Warren, as she quickly became a voice for republicanism and civic virtue—key qualities central to Republican Motherhood.

At the start of 1787, John Adams was in England as a diplomat for the United States. Abigail Adams joined her husband in 1784 after peace was secured from Great Britain. In the United States, while the Adamses were in Europe, the Constitutional Convention began without the input from John Adams. In a letter, Abigail commented on the fact that the men in Philadelphia, tasked with creation of a new Constitution, was “not terrified with the prospect of a proffligate prince to govern it appears to be in an untranquilized state.”14 Abigail feared that country was not going to come to any rational conclusion, and was further frustrated that her own husband was unable to be at the convention. However, the two women saw their disagreements in light of the Constitution’s creation and that it was no longer about crafting a new nation but protecting the one that existed.

Both women debated with each other on how the United States was going to be preserved. Warren was unsure of how the new government was going to be formed. In a letter, Warren encouraged John Adams to view the Constitutional Convention, and politics itself, with three perspectives: full support of the new Constitution, total opposition to it, and the third who “will decidedly support whatever they think right: or that tends to the General welfare.”15 Abigail Adams was confident that even though her husband was not at the convention, the civic inspiration of the Greeks and Roman was going to helped the United States obtain its highest civic virtue.16

There was a significant gap between the letters Abigail Adams and Mercy Warren wrote to one another. The reason for this gap is unclear; however, a possibility is that by 1790, the two women lived close enough to engage one another. Nonetheless, Mercy Warren often wrote to John Adams about politics and told him what his future was in the wake of the ratification of the new Constitution. John Adams suspected, through friends and correspondence, that he was going to be Vice-President under the new Constitution. Adams wrote about his ideas of an American identity and “Spirit of Union” that was prevalent in America. With the new Constitution, John Adams realized, “The Resources of this Country are abundantly Superiour to every Exigency and if they are not applied, it must be owing to a Want of Knowledge or a Want of Integrity.”17

While Warren did not respond to this directly, she implied that her son was a “Victim to public Virtue” that carried “the Determined system of political enmity that has ransacked the lower Regions.” Warren claimed her son was an individual who carried the ideals of Republican Motherhood—civic virtue and dedication to patriotic values—to his own life and career as a lawyer. She rapidly pushed against these ideas in favor of her son who “never deviatied from the line of probaty in public or in private life.”18 This developed an American identity for Mercy Warren because she raised her son to have values of a civic identity, patriotism, and dedication to country. Even though she believed politicians were dishonest with her son, she knew that that the country she raised her son in, her ideals and intentions, all related to motherhood and being an American.19 An American identity came quickly for Warren because she began the ideals from her own childhood and instilled them into her own children. It was easy for her to recognize that civic virtue and intentional patriotism was part of who she was, and thus, became her identity. Being a mother helped Warren identify these ideals further.

Abigail Adams felt a similar way, as she was fond of her son John Quincy Adams who she believed was necessary to carry on the legacy of her ideals.20 John Quincy was a diplomat in the Early Republic, and she made sure that his duties were kept with promise and intrigue. It was why she let John Quincy as a boy go with his father when John Adams negotiated peace for the United States during the American Revolution in the 1780s. She knew he was going to be an individual grown to the highest ideals of a man and American citizen. More than anything, she was proudest of John Quincy.

She never saw him become president because of her death, but she witnessed many accomplishments of his that proved that her assumptions were right. These moments became the craft of Abigail’s own identity as an American. Beyond her husband’s accomplishments, John Quincy was the spitting image of all the ideals she set for him as a boy. Even as a grown adult, Abigail never stopped encouraging the ideals of republicanism to her children. In a letter in 1790 when John Quincy established his law office, she offered him some useful advice—fresh from the republican values she established early on in his life:

Be patient and persevering. you will get Buisness in time, and when you feel disposed to find fault with your stars, bethink yourself how preferable your situation to that of many others, and tho a state of dependance must ever be urksome to a generous mind, when that dependance is not the effect of Idleness or dissapation, there is no kind parent [bu]t what would freely contribute to the Support and assistance of a child in proportion to their ability.21

When John Adams won the presidential election of 1796, Mercy Warren wrote to Abigail several months later in March of 1797 to congratulate and grieve for her on his victory. Warren wrote that “my Gratulations on mr Adams elevation to the presidential Chair are secondary to my Condolence,” which offended Abigail. Not only did Warren insult her husband when she called it a condolence, but the letter was months too late for her liking. On inauguration day, Abigail Adams replied to Warren so she could “accept my acknowledgments, considering it as the voluntary and unsolicited Gift, of a Free and enlightned people” and “every virtue of the Heart, to do justice to so sacred a Trust. Yet however pure the intentions, or upright the conduct, offences will come.”22

The friendship of Warren and Abigail began to deteriorate after John Adams’ election to the presidency. Warren’s political views contrasted with both Adamses and she felt disconnected to them. While Warren largely disagreed with John Adams use of executive power, she remained cordial with both of them. Friends who disagreed, but endured tribulation at every corner. When John Adams passed the Alien and Sedition Acts that allowed the imprisonment of journalists and deportation of anyone deemed dangerous, Warren worried. She worried for the new Republic, and realized that her friend, John Adams, was the result when executive power was too powerful.23 John Adams was unable to recover from the violation of the First Amendment that he swore to protect and was not reelected in 1800. A somber Adams Family retired to Peacefield in Quincy, Massachusetts where politics was at the back, and reflection started in the forefront.

The death of the Warren-Adams friendship started after Adams retired from public life. In 1805, Mercy Otis Warren wrote the first full length history of the Revolution titled History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. Her story was three volumes, and she interviewed and corresponded to many people of the Revolution including Jefferson and Adams to provide an honest reflection of the war. While Warren labeled the book “the new and unexperienced events exhibited in a land previously blessed with peace, liberty, simplicity, and virtue,” she was influenced by the Republican party that she belonged to.24 While scholarly in writing, her historical arguments were nationalistic and interpreted with crucial influence from the Republican party. One of her largest critiques was to John Adams, who she wrote has as a “partiality for monarchy,” which was a common criticism.25 This was the first time that Adams heard from Warren about her issues with him, and this discouraged him. Furthermore, Abigail Adams was also hurt by these allegations. John Adams, however, defended his honor and the Republican principles he helped fight for.

When John Adams wrote to Warren to debate her book, it was from a place of initial friendship. Adams defended his honor and civic integrity with hostility: “If I were to measure out to others, the treatment that has been meted to me I could make wild Work with some of your Party. Shall I indulge in retaliation, or not?”26 Adams was angry, and his retaliation never came. Warren replied with frustration and defense of her own character and integrity as she was insulted but recognized that “Passions are sometimes the heavenly gales that waft us safely to port, at others the ungovernable gusts that blow us down the stream of absurdity.”27 The conversations between John Adams and Mercy Otis Warren continued to be bitter, and the relationship never recovered.

Later, in 1813, John Adams reflected on their correspondence and the book for an unfair perception of his complex legacy. Adams wrote that her book was dangerous and that “History is not the Province of the Ladies.”28 Adams was bitter about Warren’s version of his history and was confident that future historians would write the truth about him and his place in the broader Revolution.

The end of Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren’s friendship was significant, as both of them ended the relationship with love and admiration. In the midst of the American Revolution, the two women were a solace for one another and engaged in political discourse that only they understood. The perspectives of motherhood allowed them to view the depth of civic virtue in a way only they understood it. Near the end of their lives in 1812, Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren reconciled their longstanding friendship with tokens of gratitude for one another. Warren gave Abigail a lock of her hair—a sign of respect, devotion, and trust—and Abigail crafted a custom-made ring. That moment in Plymouth, Massachusetts was the last time either of them saw each other and was the closure they both needed.

With her eyesight completely gone, but her mental faculties never diminished, Mercy Otis Warren died on October 19, 1814.29 The last letter Warren wrote before she died was an olive branch to John Adams to try and reconcile their friendship. Her final literary words were an affirmation that she “shall never cease to love the children of my friends, so long as I find them worthy, good, and amiable.”30 Republican Motherhood was the fullest intentions of her life.

In December of 1816, just after Christmas, Abigail Adams came down with a severe illness that she envisioned as her last. She started to draw up her will and included pieces of her personal property to each of her children. Beyond her jewelry, gowns, cloths, and dresses that went to her daughters, Abigail Adams gave all of her investments, nearly $4,000 dollars’ worth, to her son, John Quincy Adams. After she settled her will in 1818, she caught typhus fever which was her beacon call to heaven. She died on October 28, 1818, three days after celebrating her fifty-fourth wedding anniversary with John Adams. Her only regret was that “she should like to have the family together once more.”31 Similar to Mercy Warren, her last thought was of the children she raised and the people she loved.

Republican Motherhood was the foundation for both Mercy Otis Warren and Abigail Adams. The principle reiterated that a woman’s role in the Early Republic was not just to maintain the home but to help establish an autonomous society. While so much fighting was present in politics, women played the role of equating the necessary values and virtue into the children they raised.32

Both women believed that education was the essential factor to how children were raised. Education was the essential tool to raising strong American citizens.33 Both women viewed motherhood as the most important part of their life, and even more so, believed that it was what made themselves uniquely American. Encouragement of Republican ideals and virtue allowed for both women to articulate an America where their children belonged, and where the role of women became precedent of a larger movement.

SUGGESTED READING:

Abrams, Jeanne E. First Ladies of the Republic: Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Dolley Madison, and the Creation of an Iconic American Role. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Hacker, Jeffrey H. Minds and Hearts: The Story of James Otis Jr. and Mercy Otis Warren. Amherst & Boston: Bright Leaf, 2021.

Holton, Woody. Abigail Adams: A Life. New York, NY: Free Press (Simon & Schuster), 2019.

Jacobs, Diane. Dear Abigail: The Intimate Lives and Revolutionary Ideas of Abigail Adams and Her Two Remarkable Sisters. New York: Ballantine Books, 2014.

Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America. New York: Norton, 1986

Kerber, Linda. “The Republican Mother: Women and the Enlightenment-An American Perspective.” American Quarterly 28, no. 2 (1976): 187–205. https://doi.org/10.2307/2712349.

Lewis, Jan. “The Republican Wife: Virtue and Seduction in the Early Republic.” The William and Mary Quarterly 44, no. 4 (1987): 689–721. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939741.

Murrin, John M. “A Roof without Walls: The Dilemma of American National Identity.” In Beyond Confederation: Origins of the Constitution and American National Identity, 333–48. Chapel Hill & London: University of North Carolina Press, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 1987. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807839324_beeman.16.

Smith-Rosenberg, Carroll. This Violent Empire: The Birth of an American National Identity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Travers, Len. Celebrating the Fourth: Independence Day and the Rites of Nationalism in the Early Republic. Boston: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1997. https://hdl-handle-net.ezpro.cc.gettysburg.edu/2027/heb33582.0001.001.

Zagarri, Rosemarie. “Morals, Manners, and the Republican Mother.” American Quarterly 44, no. 2 (1992): 192–215. https://doi.org/10.2307/2713040.

Mercy Otis Warren to Abigail Adams, July 25, 1773, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0064.

To dispel any confusion between the Adams family, Abigail Adams will be referred to by her first name, while any mention of her husband, will be referred to as “John Adams” or “Adams.” All other characters will use their last name.

Diane Jacobs, Dear Abigail: The Intimate Lives and Revolutionary Ideas of Abigail Adams and Her Two Remarkable Sisters (New York: Ballantine Books, 2014), 120.

Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (New York: Norton, 1986), 9.

Republican Motherhood was not a term that was used by anyone in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries but coined in 1976 by historian Linda K. Kerber. The term is a philosophical idea to help describe the role women played in the Early Republic. This paper will use the term frequently to emphasize the argument and should not be mistaken as a phrase used by Adams, Warren, or any other person of the Early Republic.

Abigail Adams to John Adams, March 31, 1776, Adams Papers, Electronic Edition, Massachusetts Historical Society, https://www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=L17760331aa

Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic, 111; 159.

Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic, 73-74.

Warren to Adams, July 25, 1773

Abigail Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, December 5, 1773, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-01-02-0065

Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic, 139

Abigail Adams to John Adams, July 5, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-03-02-0279

Jeffrey H. Hacker, Minds and Hearts: The Story of James Otis Jr. and Mercy Otis Warren (Amherst & Boston: Bright Leaf, 2021), 127–31

Abigail Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, May 14, 1787, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-08-02-0019

Mercy Otis Warren to Abigail Adams, September 22, 1787, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-08-02-0069

Diane Jacobs, Dear Abigail, 276–77

John Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, March 2, 1789, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-19-02-0276

Mercy Otis Warren to John Adams, April 2, 1789, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-19-02-0285

Jeffrey Hacker, Minds and Hearts, 127; Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, This Violent Empire: The Birth of an American National Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 136–40.

Diane Jacobs, Dear Abigail, 429.

Abigail Adams to John Quincy Adams, August 20, 1790, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-09-02-0049

Mercy Otis Warren to Abigail Adams, February 27, 1797, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-11-02-0302; Abigail Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, March 4, 1797, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-12-02-0004

Jeffrey H. Hacker, Minds & Hearts, 206-207.

Mercy Otis Warren, History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution (Boston: Manning & Loring, 1806), vol. 1, https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/thomas-jeffersons-library/interactives/history-of-the-american-revolution/.

Jeffrey H. Hacker, Minds & Hearts, 213.

John Adams to Mercy Otis Warren, July 11, 1807, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5193

Mercy Otis Warren to John Adams, July 16, 1807, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-5194

John Adams to Elbridge Gerry, April 17, 1813, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6000

Jeffrey Hacker, Minds & Hearts, 215-216.

Mercy Warren to John Adams, August 4-11, 1814, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-6324

Woody Holton, Abigail Adams: A Life (New York, NY: Free Press (Simon & Schuster), 2019), 405–11.

Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815, vol. 2, Oxford History of the United States (Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 502–3.

Jeanne E. Abrams, First Ladies of the Republic: Martha Washington, Abigail Adams, Dolley Madison, and the Creation of an Iconic American Role (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 125–26.

Fantastic! Thanks for sharing the piece.