Abraham Lincoln’s Quiet Burden

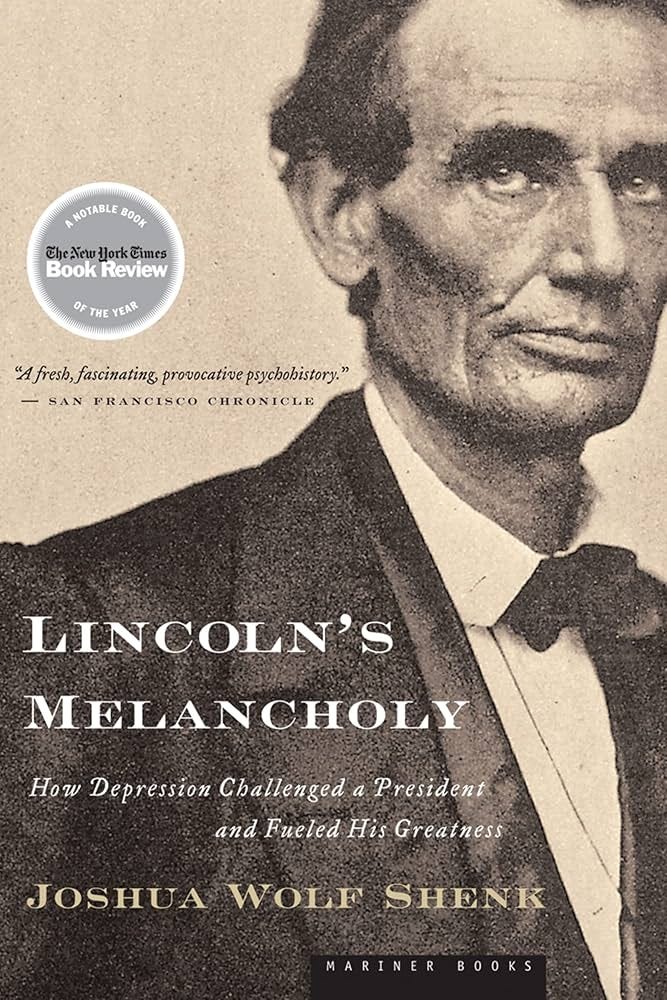

A Review of Joshua Wolf Shenk’s "Lincoln’s Melancholy"

Some works do not simply inform you. They change the angle of your vision. Joshua Wolf Shenk’s Lincoln’s Melancholy arrived in my life at exactly such a moment. Years before I stood in front of a classroom, long before I began writing about history for others, this book introduced me to the idea that the inner world of a historical figure could be just as significant as the outward events that fill textbooks. It taught me that a life is more than a chain of dates and accomplishments. It is also a story made of long shadows and quiet struggles, of emotions that leave their marks on private thoughts and public choices. That insight helped shape my decision to become an educator. I wanted to teach students that history is not only what people do. It is also what people feel.

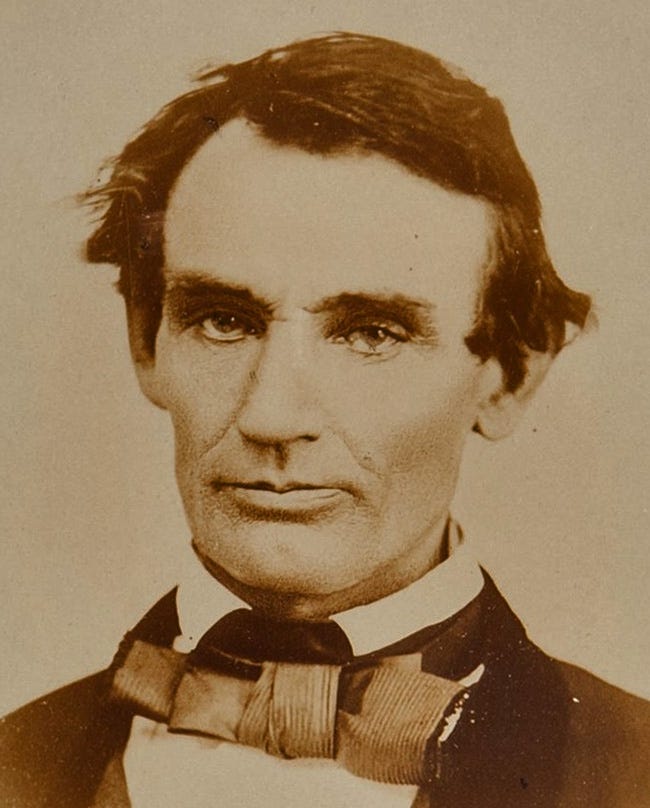

Shenk presents a vision of Abraham Lincoln that is richer and more troubling than the common narratives many readers inherit. Rather than portraying Lincoln as a granite figure who stood above despair, he shows a man who lived with melancholy as a constant presence. This melancholy did not flatten him. It shaped him. It cultivated a capacity for reflection, endurance, and moral depth. Lincoln’s sorrow became one of the forces that made him the kind of leader the nation required during its deepest crisis. This is the argument that moves quietly but steadily through the book, and it remains one of its most compelling contributions to Lincoln scholarship.

Shenk grounds his interpretation in sources that reveal Lincoln’s psychological landscape with striking clarity. He draws from private letters, recollections of friends, early poetic fragments, and newspaper accounts that hint at the internal storms Lincoln weathered in his youth and adulthood. In 1841 Lincoln admitted that he had entered “the worst state I have ever experienced.”1 This was after his longtime love passed away. Such a sentence carries no ornament. It is honest, direct, and painfully human. It is also one of the strongest pieces of evidence that Lincoln experienced periods of emotional collapse that shaped his sense of self.

Among the most evocative artifacts associated with Lincoln’s inner life is the poem known as the Suicide Soliloquy. Published anonymously in an Illinois newspaper in the 1830s, it was later linked to Lincoln through local recollection and stylistic similarities. The poem opens with bleak intensity and captures the voice of someone confronting the overwhelming weight of sorrow. It speaks of a heart “sickened with sorrow” and a life “weary of breath.”2 Scholars still debate authorship, but the raw emotion in the poem aligns closely with accounts of Lincoln’s periodic despondency.

The speaker in the Suicide Soliloquy is a very different figure. He is vulnerable, frightened, and uncertain about the purpose of his own existence. Even those students who question whether Lincoln wrote the poem often conclude that it captures a truth about the emotional world he inhabited. The poem becomes a window into the interior life of the young Lincoln, a glimpse of the storms he had to learn to survive:

Here, where the lonely hooting owl Sends forth his midnight moans, Fierce wolves shall o’er my carcase growl, Or buzzards pick my bones. No fellow-man shall learn my fate, Or where my ashes lie; Unless by beasts drawn round their bait, Or by the ravens’ cry. Yes! I’ve resolved the deed to do, And this the place to do it: This heart I’ll rush a dagger through, Though I in hell should rue it! Hell! What is hell to one like me Who pleasures never know; By friends consigned to misery, By hope deserted too? To ease me of this power to think, That through my bosom raves, I’ll headlong leap from hell’s high brink, And wallow in its waves. Though devils yell, and burning chains May waken long regret; Their frightful screams, and piercing pains, Will help me to forget. Yes! I’m prepared, through endless night, To take that fiery berth! Think not with tales of hell to fright Me, who am damn’d on earth! Sweet steel! come forth from our your sheath, And glist’ning, speak your powers; Rip up the organs of my breath, And draw my blood in showers! I strike! It quivers in that heart Which drives me to this end; I draw and kiss the bloody dart, My last—my only friend!

Shenk takes this emotional history and demonstrates how it shaped Lincoln’s public life. Rather than treating melancholy as a private hindrance to overcome, Shenk argues that it developed Lincoln’s patience and helped form the moral seriousness that defined his leadership. Melancholy taught Lincoln to reflect deeply. It taught him to temper passion with thought. It taught him to find clarity even when his own heart carried its own wounds. These habits became essential when he confronted the terrors of civil war.

Lincoln’s writing reveals this connection with remarkable consistency. In April of 1862 he wrote to General McClellan, “If you do not want to use the army, I should like to borrow it for a while.”³ The line is often quoted for humor, but the emotional tone beneath it matters more. The calm, almost weary patience in Lincoln’s language is the product of someone who has learned how to face frustration without letting it dominate him. He expresses urgent need without harshness. He presses forward with clarity rather than bitterness. When I teach this letter, students often notice how different Lincoln sounds from the romantic images they carry of him. They begin to see him not as a symbol, but as a person whose emotional life has formed his public voice.

Another element of Lincoln’s emotional discipline lies in his use of coping strategies. Shenk notes that Lincoln relied on humor as release, on routine as stability, and on close friendships as grounding forces. These practices were not incidental to his leadership. They were the tools that enabled him to endure. His steadiness during the war was not the absence of suffering. It was the product of years spent learning how to live with it.

This understanding reshapes how one reads Lincoln’s greatest speeches. The Second Inaugural Address, often regarded as one of the most profound meditations on national sin and redemption, takes on new meaning when viewed through the lens of melancholy. When Lincoln observed that “every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword,” he spoke not with vindication but with sorrow.3 He understood the cost of suffering because he had lived so long in its company. Beneath the moral clarity of the speech lies a heart shaped by grief. Recognizing that emotional foundation deepens the impact of his words. It makes his appeal to national humility and reconciliation even more powerful.

This is why Shenk’s work remains so valuable for teaching. Students are often surprised to learn that historical figures possessed inner worlds as complicated as their own. When they encounter Lincoln not as the untouchable figure from coinage and sculpture but as a man who battled despair, they discover a more approachable and more profound version of history. They begin to ask better questions. They begin to see how emotional life shapes decisions. The study of Lincoln’s melancholy reveals that history is not a collection of outward events alone. It is also the record of how individuals wrestle with themselves.

Primary sources play an essential role in this process. The Suicide Soliloquy becomes a doorway into psychological history. The letter to McClellan becomes an example of emotional restraint in leadership. The Second Inaugural becomes a testament to how sorrow can lead to moral wisdom. Through these documents students learn that Lincoln’s leadership did not emerge from an absence of feeling. It emerged from the depth of it.

Shenk’s work succeeds because it maintains a careful balance between psychological interpretation and historical grounding. He does not romanticize Lincoln’s despair, nor does he exaggerate its influence. Instead, he presents a portrait that is textured, evidence based, and deeply humane. The book expands the possibilities of how we write about the past. It reminds us that emotional history is not peripheral. It is essential.

As a result, Lincoln’s Melancholy remains one of the most meaningful works I return to. It shaped the way I understand biography and the way I teach. More importantly, it shaped the way I understand Lincoln. It revealed a man who did not avoid sorrow, but who learned how to live in honest conversation with it. That discipline, that interior labor, became part of the strength that carried the nation through its darkest moment.

This is the Lincoln that Shenk offers. Not the marble figure of legend, but a human being whose greatness arose not in spite of his melancholy, but through it. For readers seeking a deeper understanding of Lincoln’s inner life, or for those who simply wish to see how sorrow can become a source of wisdom, this book remains indispensable.

Abraham Lincoln. Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916: Charles F. Anderson, Monday,Extract of Appropriations Act. 1850. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mal0047500/.

Joshua Wolf Shenk, Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness, Houghton Mifflin, 2005, pp. 33 to 36.

Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865. The Avalon Project, Yale Law School: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/lincoln2.asp