Ken Burns and the Meaning of the American Revolution

Reflections on Historical Memory and the Approach of the 250th Anniversary

Ken Burns has spent more than forty years shaping the way Americans encounter their own history. His films have become familiar cultural objects that blend voices, music, images, and commentary into narratives that attempt to unify rather than divide. In the lead up to the release of The American Revolution he declared that the Revolution was the most important event since the life of Christ and that this documentary could help unite the nation. These statements reveal his longstanding belief in American exceptionalism, a belief that has often guided the way he frames historical subjects. Before watching the first two episodes I worried that this instinct would shape the narrative too strongly. My concern was not that he would ignore complexity, but that he might place the Revolution in symbolic stone and emphasize myth over the full reality of eighteenth century experience.

To my surprise the documentary ventured in a different direction. From the opening minutes the presence of Native Americans, enslaved people, and the wider Atlantic world is unmistakable. Rather than appearing as marginal figures they occupy the center of the story. Their voices are woven into the political and military developments in a way that recognizes their importance and restores them to positions of historical influence. This relieved my concern that Burns might offer a comforting patriotic story that overlooks the complex inequalities that shaped the era. If anything, the work is far more sensitive to these issues.

My own training as a historian lies in Early American New England. The region’s political culture, Indian confederacies, racial dynamics, and the Atlantic world have long been at the center of my research. The documentary spends considerable time in this landscape and captures many of the essential forces that shaped it. The towns of Massachusetts, the pressure of Native alliances, and the presence of slavery in New England appear throughout the first two episodes. Watching the documentary through this lens gave me the opportunity to consider the production not as a casual viewer but as someone with disciplinary commitments and expertise. The documentary touches the corners of the field that I know well, and in doing so it invites a more careful reflection about the strengths and limits of Burns’ approach.

The Story That Was Told

The documentary presents the Revolution as a convergence of several interpretive traditions. It is a conflict over land, political rights, social tensions, and competing visions of liberty. It is also an ideological struggle in which colonists brought together legal, philosophical, and religious ideas to justify resistance against British authority. Burns attempts to tell all these stories at once, but he keeps the political story firmly in the foreground. Battles appear, but they are secondary to the broader context and do not overwhelm the documentary. This decision mirrors current scholarship, which seeks to balance political and military history with social, cultural, and racial histories. The result is a narrative that avoids dominance by any single interpretation.

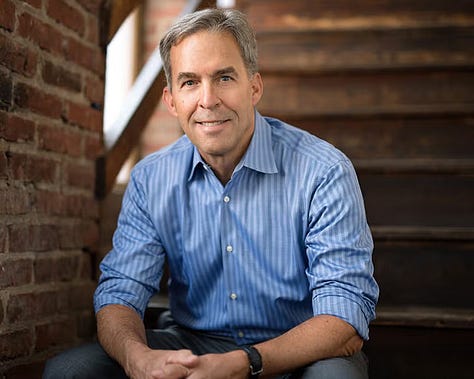

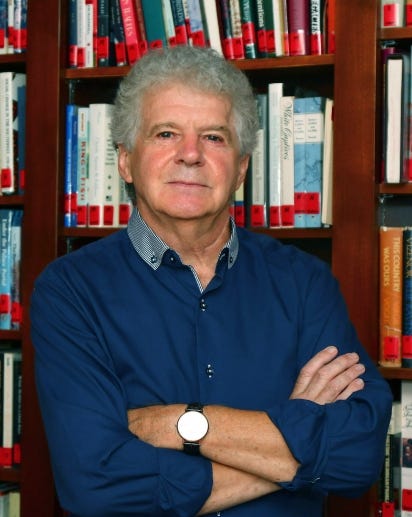

Much of the success of the early episodes comes from the selection of historians. Burns has often been criticized for leaning too heavily on one voice, but this time he provides a wide range of perspectives that reflect the rich diversity of the field. Bernard Bailyn appears in the first episode, a meaningful choice because his work reshaped the study of the Revolution in the mid twentieth century. His argument that ideas lay at the heart of the conflict remains central to scholarly debate. Pairing him with Gordon Wood and Joseph Ellis reinforces this intellectual tradition.

Alan Taylor, whose transatlantic framework influenced my own path into Early American studies, offers a counterbalance. His work insists that the Revolution was a continental and Atlantic story, shaped by migration, Indigenous diplomacy, imperial competition, and environmental change. His presence in the documentary broadens the frame beyond the thirteen colonies and situates the conflict within the larger world that shaped it.

Other historians deepen the interpretation. Ned Blackhawk explains Native strategies during the imperial crisis. Annette Gordon Reed emphasizes the racial and legal contradictions that defined the era. Colin Calloway focuses on documents and the motivations of Indigenous leaders. Christopher Brown and Rick Atkinson contribute military insight. Kathleen DuVal, Jane Kamensky, and Serena Zabin reveal the social and cultural forces that rose to the surface as conflict intensified. This varied collection of voices gives the documentary a sense of scholarly richness and continuity. For a historian it feels like entering a room filled with colleagues whose work has shaped the field for decades.

The primary sources provide the emotional and intellectual foundation of the story. Burns uses letters, diaries, poems, and political documents to animate the era. The voice acting is particularly effective because it gives the sources texture and immediacy. Phillis Wheatley appears early, and Amanda Gorman’s reading of her poetry creates one of the most memorable moments of the opening episodes. Many viewers will be unfamiliar with Wheatley’s presence in Revolutionary Boston or her connections to its political culture. Bringing her voice forward is not only accurate but essential to understanding the intellectual world of eighteenth century Africans in America.

The presentation is strong, although the documentary sometimes moves quickly over longer passages without displaying the full text on the screen. For academic readers this can feel rushed. Many of us prefer to see the full quotation to parse the language and context. Yet for general audiences this choice prevents visual clutter and keeps the pacing manageable.

Some simplification is inevitable in a documentary of this size. Burns is not attempting to resolve historiographical debates. His goal is storytelling grounded in evidence. He relies on the expertise of historians rather than formal argumentation. This may disappoint some specialists, but it aligns with the expectations of the format. What stands out is that Burns has become more careful as his career has progressed. He no longer adopts broad interpretive claims without acknowledging complexity. The criticisms that followed The Civil War concerning the Lost Cause tradition have made him more attentive to scholarly responsibility. Here he makes a visible effort to respect accuracy while still creating an accessible narrative. It is clear he wants the series to speak to both historians and general audiences as the nation approaches its semiquincentennial.

The representation of diverse communities is one of the great strengths of the series. Native nations appear not as victims of imperial expansion but as political actors who shaped the course of the conflict. Enslaved people and free African Americans appear throughout, not only as symbols of contradiction but as individuals with agency and influence. Women appear as political commentators and observers with insight, not as background figures. This inclusiveness is handled with care. It does not feel forced or ornamental and instead feels like an acknowledgment of the reality that the Revolution was always a story of many peoples, not simply a story of elite politicians.

The aesthetic quality of the documentary is impressive. The musical score blends original pieces with period music and creates a sense of atmosphere that never feels overwhelming. The sound editing during the Battle of Lexington and Concord in particular captures the fear and confusion of the moment. The visuals make excellent use of archival images and landscapes. Some sequences feel long, but the slower pacing allows space for reflection rather than spectacle.

There are places where the documentary moves quickly, but this is a matter of pacing rather than interpretation. Burns appears far more careful with accuracy here than in earlier decades. The documentary is not intended only for experts but is meant to bring a wide audience into contact with scholarship that has developed over the last half century. Burns has said that the series should spark conversation. That ambition requires a balance between scholarly depth and narrative clarity, and he generally achieves that balance.

What this documentary offers the public is a chance to revisit the American Revolution from perspectives that most viewers have never encountered. Too often the Revolution is told as a story that centers on political leaders while treating Indigenous peoples, African Americans, women, and ordinary colonists as background. Burns resists that habit. He tries to present the Revolution as a complex world of competing visions and lived experiences. This matters because public memory shapes national identity. As the 250th anniversary nears, the way we talk about the Revolution will influence how we understand ourselves. Burns’s documentary happens to arrive at precisely the moment when a national conversation about the meaning of the Revolution is needed.

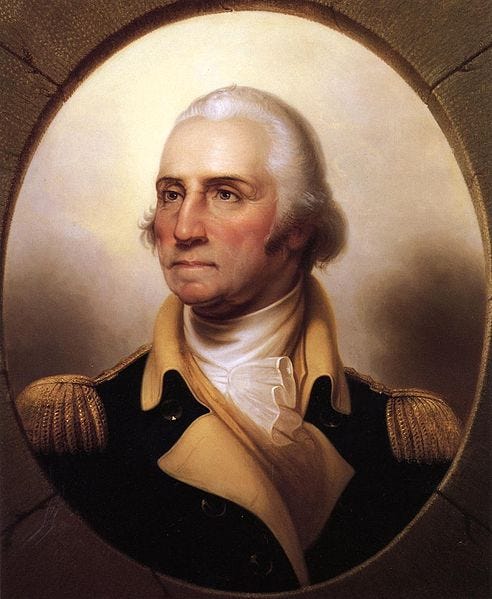

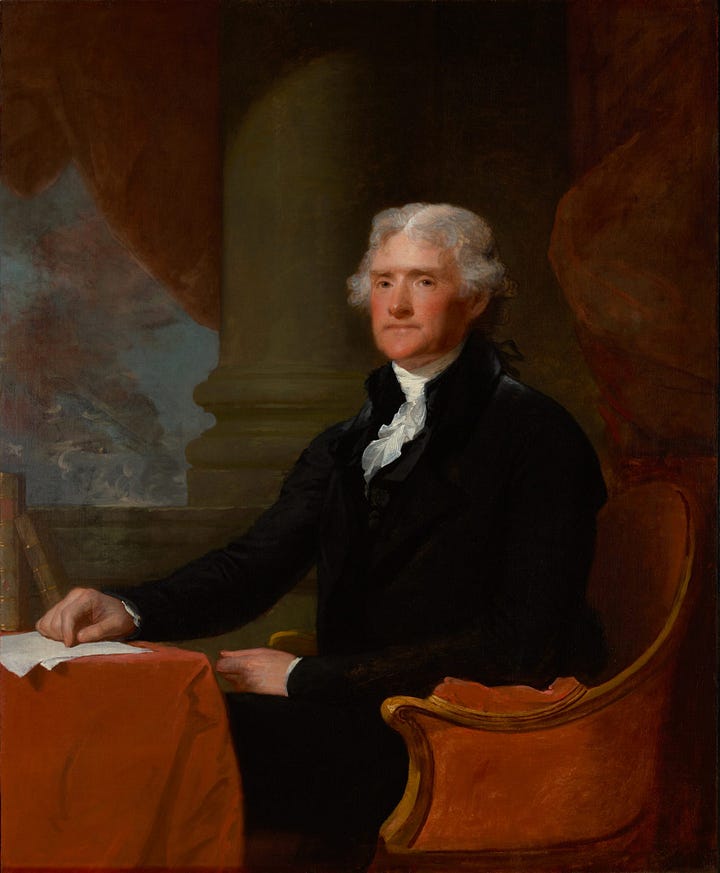

The documentary does not simply reproduce national myth. If anything, it complicates that myth by acknowledging the contradictions within the Revolutionary era. His press comments might suggest a more celebratory approach, but the documentary itself is far more balanced. It recognizes the presence of injustice and inequality. It acknowledges that figures like Washington and Jefferson held enslaved people and that their legacies carry inherent contradictions. Burns lets historians and documents speak for themselves, which allows viewers to form their own interpretations.

General audiences will embrace the documentary in the usual way. Many will find in it a familiar sense of coherence and clarity. Historians will watch with different expectations. They will note the choices, omissions, and emphases that shape the narrative. Yet they will also recognize the documentary as a work of public history that brings serious scholarship into the world of popular media. That contribution is significant because it encourages viewers to look beyond the familiar patriotic frame and consider the Revolution as a human story filled with conflict, hope, and uncertainty.

As the two hundred fiftieth anniversary approaches, the question of how we remember the Revolution will become more pressing. The semiquincentennial will likely be marked by celebration, reflection, and political tension. Burns documentary feels like the first major contribution to that moment. It offers an invitation to reconsider the meaning of the Revolution and to think about what its ideals might still offer today. The past is not fixed in marble, but a living subject that changes as we ask new questions and encounter new evidence. A national anniversary should encourage honest conversation, not rote celebration.

Burns’s documentary begins that conversation. It reflects the progress of scholarship, acknowledges the diversity of Revolutionary experience, and provides an accessible narrative that invites viewers to engage with a complicated past. It is not perfect, but it is necessary. It will shape public understanding, provoke discussion, and remind viewers that the Revolution was not a singular achievement but a contested process. As we move toward the semiquincentennial, this documentary may serve as a guide to thoughtful engagement. It offers a way to look back with clarity and to look forward with curiosity and a willingness to consider the many forces that created the United States.

SUGGESTED READING:

Remember to always support your local bookstores.

*******

Alan Taylor, American Colonies. New York: Viking, 2002.

Alan Taylor, American Revolutions: A Continental History. New York: Norton, 2016.

Annette Gordon Reed, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. New York: W. W. Norton, 2008.

Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Collin Calloway, The Indian World of George Washington. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

David Waldstreicher, The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journey Through American Slavery and American Independence. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023.

Rick Atkinson, The British Are Coming: The War for America, Lexington to Princeton. New York: Henry Holt, 2019.

Serena Sabin, The Boston Massacre: A Family History. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020.

Phillis Wheatley, Vincent Caretta (editor), Complete Works. New York: Penguin Classics, 2001.

Nicely said.